INTRODUCTION

The CDC lists assessing and monitoring community needs and addressing health problems affecting the population among the 10 essential health services necessary to properly care for the health of a community.1 The community health needs assessment (CHNA) is one primary research method for monitoring and investigating the health concerns of a community.2 The practical execution of a CHNA can present significant challenges, particularly when considering the complexities introduced by cultural and language barriers. These barriers can impede effective communication between healthcare providers and community members, potentially leading to misunderstandings about health issues and hindering the collection of accurate information.3 Furthermore, cultural differences can influence health beliefs, behaviors, and the perception of health needs, adding another layer of complexity to the assessment process.4

Despite these challenges, a diverse, interdisciplinary team consisting of University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA) medical students, physicians, and community members developed and conducted a CHNA at an annual health fair held by the El Bari Community Health Center (El Bari CHC). The El Bari CHC is a free clinic that serves patients without health insurance and provides free health screenings at its annual fair held at the Muslim Children Education and Civic Center (MCECC). To overcome the barriers mentioned previously the CHNA was administered uniquely, translators were present to aid respondents. Furthermore, after completing their surveys anonymously, respondents’ top three health priorities and barriers were displayed on color-coded posters, combining community responses. Aggregating responses helped alleviate cultural barriers by minimizing fear of judgment and eliminating groupthink. At the end of the health fair, these posters were displayed for all attendees.

Through the CHNA, nutrition was identified as the top community health priority. Meetings between community members and the UTHSCSA team discussing how to address the community’s needs led to the creation of the Healthy Choices Team (HCT). The HCT serves a culturally diverse community in Bexar County, Texas. To address community-identified priorities, the HCT fosters sustainable behavior change in nutrition, exercise, sleep, and mindfulness by connecting community members to experts and empowering participants to become future ambassadors of healthy living within their communities.

The HCT administers a core curriculum consisting of twice-monthly sessions from Fall-Spring led by community members, health professionals, and health science students with a focus on nutrition, healthy cooking, and promoting other positive lifestyle habits. It culminates with a graduation for community members who attended most sessions. Graduates are then invited to return the next year as ambassadors and help bring in new participants and encourage engagement from community members, helping maintain continuity between cohorts.

The HCT has completed its fifth year of service. The leadership team has grown to include family medicine physicians and residents, registered dietitians, as well as medical, dental, PT/OT, dietetic, and pre-medical students. From its inception and throughout the program, the HCT has collaborated with multiple community organizations in San Antonio, including the El Bari Community Health Center, Bexar Translational Advisory Board, and the Raindrop Foundation. In addition to the core sessions, other initiatives have included sessions on healthy cooking during Ramadan and creating a blog of healthy recipes reviewed by dietitians. The HCT has built a community of individuals that share their healthy habits and lifestyle changes through a common WhatsApp group moderated by HCT. This paper aims to analyze survey data from across all five years and find the areas it has been most effective in educating and engaging the community. This information will be used to improving the program and to serve as a model for community-based interventions.

METHODS

After analyzing the CHNAs, the design of the HCT was adapted from the Community Health Club model, voluntary organizations free of charge to community members of all ages, education levels, sex, and status that create community cohesion and a health culture through open dialogue and accountability.5,6 Like the model, the HCT was free, open to all adults, and encouraged bidirectional learning between facilitators and members. However, the HCT had biweekly meetings and sessions were led by an interdisciplinary team rather than community health workers. The curriculum ran from Fall to Spring with seven to nine sessions, most in-person with a hybrid approach via Zoom. The curriculum was adapted from the Salud Con Sabor Latino Curriculum, with sessions on mindful eating, dental health, physical activity, sleep, and healthy adaptations to popular recipes from the South Asian community.7 Participants were recruited through advertisements at the MCECC and word of mouth by ambassadors.

Each year, a pre- and post-survey were administered via Redcap at the first session and following the final session, respectively, consisting of questions assessing participant health knowledge, attitudes, and habits.8,9 The survey administered is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. Questions were categorized into themes like dietary habits and social determinants of health. In Year Four, surveys were updated to reflect community-driven ideas like physical activity, and curriculum content was modified based on these findings. Chi-squared tests were performed on the data for statistical analysis, given its categorical nature.

RESULTS

Three CHNAs were initially conducted at the 2018, 2019, and 2023 El Bari Health Fair. A total of 235 responses were gathered from the three CHNAs. The respondents consisted of a diverse community speaking many different languages as shown in Figure 1.

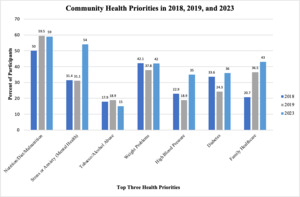

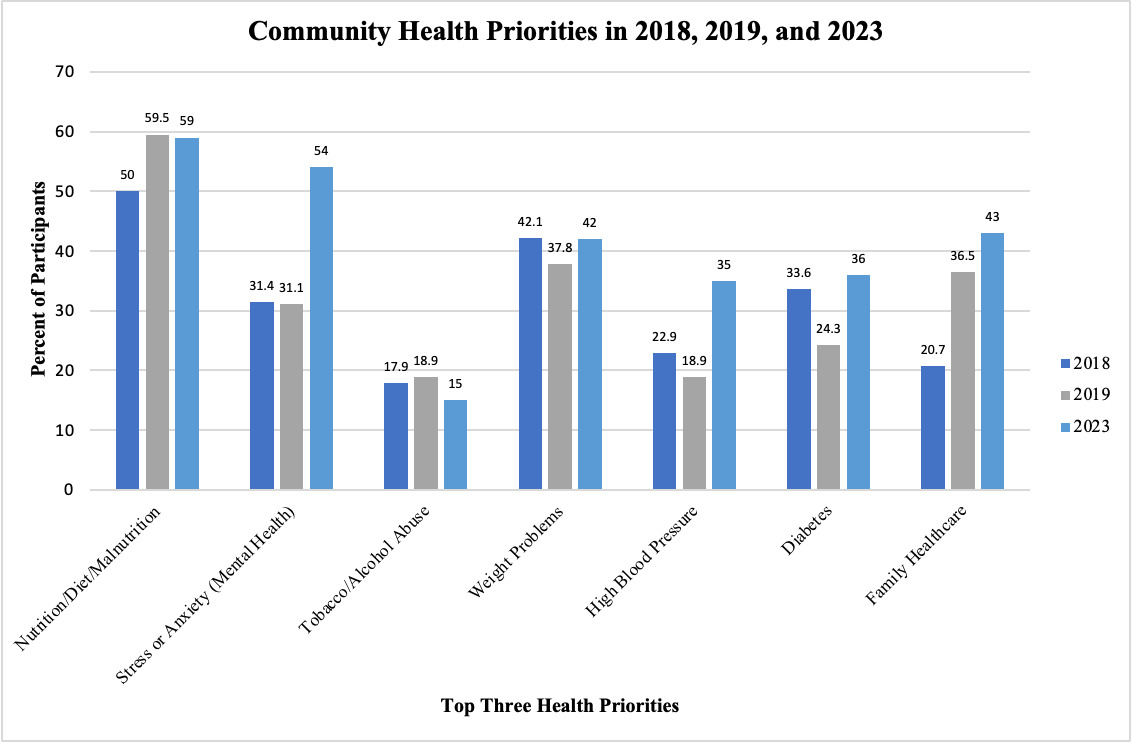

Among 2023 health fair participants, 54.5% were female with an average age of 40 years; 68.2% held a college or postgraduate degree, 52% were employed full-time, and 76.6% had health insurance. 59% of participants ranked nutrition as a top three personal health priority, while 54% and 42% of participants ranked mental health and weight management respectively. Perceived community health priorities are shown in Figure 2 while perceived community health barriers are shown in Figure 3.

From 2018 to 2023, a lack of time remained the most consistently reported health barrier. Notably, access to healthy food—previously a top barrier—significantly declined in frequency (chi-square=16.026; p=0.0003) in 2023. Interestingly, a trend in health concerns included the rise of mental health as a community-wide health priority (chi-square=14.871; p=0.0006), reflecting shifts possibly accelerated by stressors resulting from the pandemic. These results underscore enduring health barriers, particularly time constraints, while showing changes in health priorities. This highlights the need for an invention that works with the community and adapts to its changing needs.

Out of 194 total participants attending the HCT sessions, 103 community members graduated across its first five years, with several community members returning as ambassadors. Participants came from a variety of backgrounds. Based on pre-survey data, most participants over the first five years reported their ethnicity as South Asian, seen in Figure 4, and reported Urdu as their primary language other than English as shown in Figure 5. Other ethnicities included Middle Eastern and Hispanic/Latino, and participants spoke 17 different languages across all years. Participants’ ages ranged from 18-80, with a median age of 43. Ages were skewed toward young or early middle adulthood, with around 70% of participants being under the age of 50. Most participants each year were female, with an average across all five years of 70% female and 30% male. The highest level of education completed by participants was most frequently reported as college (39% across all years) or post-graduate (33% across all years). Slightly more than half (51%) of participants reported a household size of five or greater members including themselves.

Each year’s pre-surveys included questions on health habits such frequency of tracking sodium consumption and reading nutrition labels. This data was compared to post-survey data to assess whether there were changes in participants’ self-reported health habits. Only data from participants who responded to both pre- and post-surveys was analyzed; samples sizes for the matched data are n = 34 for Year One, n = 25 for Year Two, n = 21 for Year Three, n = 13 for Year Four, and n = 17 for Year Five. In addition to nutrition, the community expressed interest in learning about physical activity, so Years Four and Five surveys include questions about this topic that were not asked in previous years.

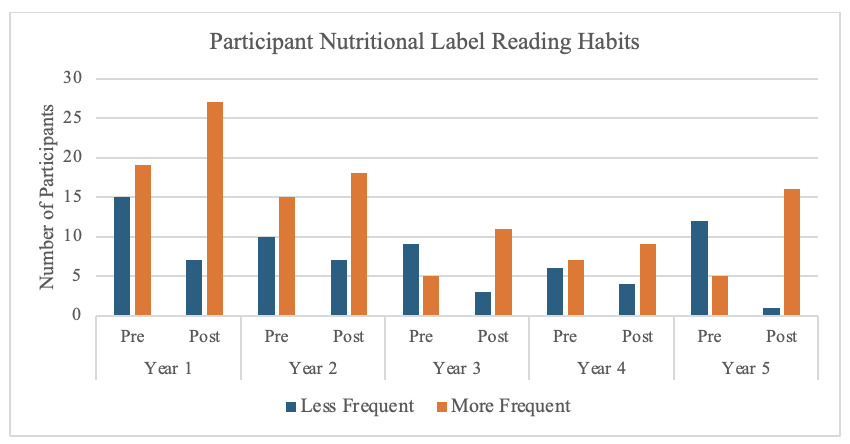

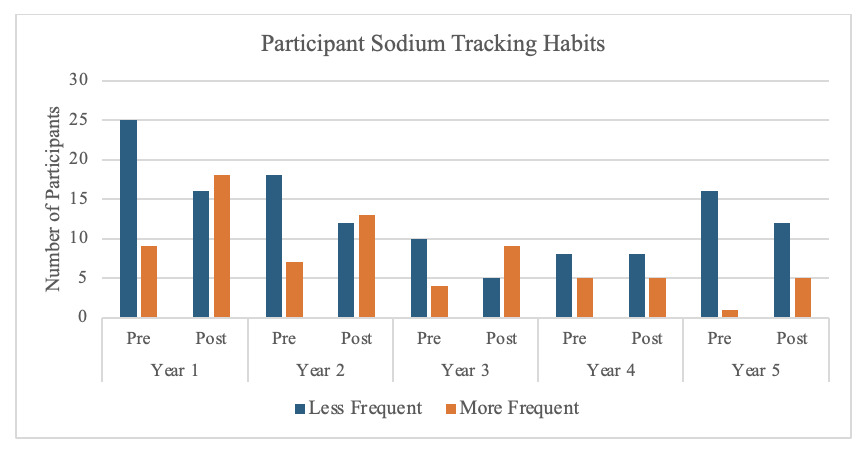

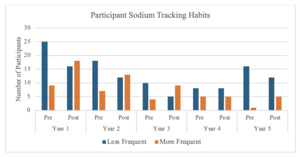

Given that the focus of one of the HCT sessions is reading nutrition labels, participants were asked to report how frequently they read nutrition labels. Pre/post-survey comparisons showed participants consistently reported reading nutrition labels significantly more often at the end of the program, with a percent increase from less frequently (calculated by summing the number of participants who answered never/occasionally/sometimes) to more frequently (calculated by summing the number of participants who answered usually/often/always) by 24% in Year one, 12% in Year two, 43% in Year three, 15% in Year four, and 65% in Year five. These results are shown in Figure 6. Furthermore, participants also significantly increased their frequency of tracking sodium intake most years, with a percent increase from less frequently (calculated by summing the number of participants who answered never/occasionally/sometimes) to more frequently (calculated by summing the number of participants who answered usually/often/always) 26% in Year one, 24% in Year two, 36% in Year three, no change in Year four, and 24% in Year five as shown in Figure 7.

In addition to improved nutritional health habits, participants also demonstrated healthier physical activity habits. Participants were asked to describe their activity level before and after completing the HCT program as either sedentary (spend most of the day doing daily chores with < 30 minutes of intentional moderate exercise), low active (daily exercise equivalent to about 30 minutes of walking or doing vigorous exercise for 15-20 minutes), active (daily exercise equivalent to walking for about two or more hours or vigorous exercise for less than an hour), or very active (daily exercise equivalent to walking for four hours or more or vigorous exercise for about two hours). Furthermore, participants self-reported whether they knew how to meet their physical activity goals by selecting either strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree to this sentiment. Figure 8 displays these results. Participants who answered agree or strongly agree to whether they knew how to meet their physical activity goals were grouped as confident in meeting physical activity goals; while participants who answered either strongly disagree, disagree, or neutral were grouped as not confident. Similarly, participants who answered they were active or very active were grouped as physically active whereas participants who answered sedentary or low active were grouped as not physically active. In Year Four, participants were significantly more physically active (chi-square=10.053, p=0.002) and confident in meeting their physical activity goals (chi-square=7.749, p=0.005) after completing the HCT curriculum. A similar effect was found in Year Five for both physical activity levels (chi-square=4.61, p=0.032) and confidence in meeting physical activity goals (chi-square=14.584, p=0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Understanding a community’s health priorities and barriers is an essential first step to learning about that population and pursuing appropriate interventions for positive health impact. The CHNAs conducted at the El Bari CHC Clinic Health Fair provided the first insights into this community’s demographics, health priorities, and health barriers. The novel design of the CHNA allowed respondents to reflect on their primary health concerns and challenges to health in private before viewing a poster that reflected the group’s response. CHNA results revealed nutrition as an important health concern for this community each year surveys were conducted, while time was consistently the main barrier to good health.

The goal of the HCT was to build a safe environment for communal learning and empower community members to take control of their diet choices together. Team members built a sense of ownership of the HCT by defining the time of the sessions, what ground rules they wanted to set for themselves, and providing a list of topics they hoped to cover in sessions. Furthermore, the HCT leaders included previous graduates who maintained continuity throughout the years and facilitated community involvement. Participant feedback following each session and from the post survey was taken into consideration each year to improve the program, as seen with the inclusion of physical activity sessions in latter years. The HCT intervention leveraged intrinsic and lasting motivation that are crucial for making positive health behavior change. Facilitators encouraged active listening, reflective questioning, participation in activities, and bi-directional learning between participants and the research team. Sessions were framed as discussions rather than lessons to minimize hierarchy and fear of judgement. This also allowed the research team to more insightfully view the community experience around nutrition.

In initial discussions with members, nutritional misinformation and myths were widespread. The American Dietetic Association argues that nutritional misinformation has harmful effects on the health, well-being, and economic status of consumers, and that healthcare professionals should advocate science-based nutrition.10 Our interdisciplinary team served this function with the HCT arming the community with scientifically based nutritional information. Each session included discussion on the successes and challenges of incorporating small healthy food changes in the home.

Qualitative feedback from HCT members indicated that the intervention was worthwhile and valuable. Individuals who completed both pre- and post-surveys reported improved confidence in several healthy nutrition-related behaviors, as seen in the increase of participants who began reading nutrition labels, tracking their sodium intake and increasing their physical activity levels. Even after graduating, HCT members remain engaged in discussion around nutrition on WhatsApp.

Our study had many challenges and adaptations over the five years. With most of our community being South Asian and Urdu speaking, the greatest initial challenge was building a foundation of trust with this community, who are reported to have mistrust and underrepresentation in research.11–13 By including the community in each step of the CHNA and creating a team-based environment for the interventional sessions, the research team gained trust in this community over several years. Sensitivity to the practices and perceptions of South Asian culture in this population was of paramount importance. For example, the research team always removed shoes and women wore head covers while entering the sessions to respect cultural norms. During sessions, team members served as translators when needed, and an ambassador was involved in leading every session to facilitate communication between speakers and community members. By working closely with individuals of South Asian culture for feedback on the wording and graphics of CHNAs, survey questions, and session curriculum, the research team made adaptations in each step of the process to be culturally. For example, when community members pointed out that the survey option “mental health” was perceived as poor brain health, such as dementia, the research team changed the wording of the survey in the subsequent year to specify mental health as depression or anxiety. The cultural thoughtfulness put into the survey paid its dividends in mutual respect between the research team and the community members.

One shortcoming in our methods involved post-survey completion. We chose to administer the post-survey at the final graduation celebration. Amidst the excitement, less post-surveys were completed, and some graduates never completed a post-survey. There was additional challenge in following up with graduates who did not complete the post-survey due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the smaller post-survey sample size than the pre-survey sample size, the conclusion drawn from this study might be different in the larger community.

Maintaining continuity with this community over the coming years will be integral to supporting positive health behavior change on both individual and community levels. By the later HCT sessions, members were already looking ahead to the next intervention. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, members have remained engaged since their graduation, taking turns sharing healthy family recipes for Ramadan over Zoom. The program is still ongoing and striving to make improvements. Feedback from members indicated that there is still interest in diving deeper into topics of nutrition, and that they have friends and family members who are interested in joining for a second round of the program. Sessions on topics like food groups, portion sizes, and nutrition labels will continue to be facilitated by previous HCT graduates. In this way, the Healthy Choices Team graduates now serve as nutritional leaders for their community.

CONCLUSION

The HCT program represents a successful and culturally tailored longitudinal community-based intervention to improve nutritional habits among a predominantly South Asian population. Originating from a CHNA conducted at the El Bari Community Health Center in 2018 and 2019, the program was designed in response to identified barriers and priorities, such as limited access to healthy food and nutrition as a key health concern. Over five years, HCT leveraged bi-directional learning, active community involvement, and culturally sensitive practices to create an empowering environment for participants. The inclusion of graduates as ambassadors further strengthened the program’s continuity and community engagement.

Analysis of pre- and post-surveys demonstrated positive behavior changes, including greater frequency of reading nutrition labels, improved tracking of sodium intake, and increased physical activity levels. Despite challenges like post-survey completion rates and addressing cultural barriers, the program has successfully built trust and fostered lasting behavioral change. By actively involving community members in leadership roles and fostering a culture of shared learning, HCT not only improved individual health outcomes but also created ripple effects within participants’ families and communities.

This study underscores the importance of integrating cultural sensitivity, trust-building, and community ownership into health interventions. The HCT model can serve as an effective template for other community-based programs aiming to address health disparities and foster sustainable behavior changes. Future efforts should focus on scaling the program and expanding its scope while maintaining its culturally sensitive and community-driven approach.

From the beginning this project has been conducted in collaboration with community members, who took an active role in leading the program and supporting each other’s progress. This project can serve as a model for other community-based research programs due to its longevity resulting from continued engagement of community members.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The HCT program was supported by a Community Service Learning Grant from the UTHSCSA Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

.png)

._the__other__ca.png)

._the__other.png)

.png)

._the__other__ca.png)

._the__other.png)