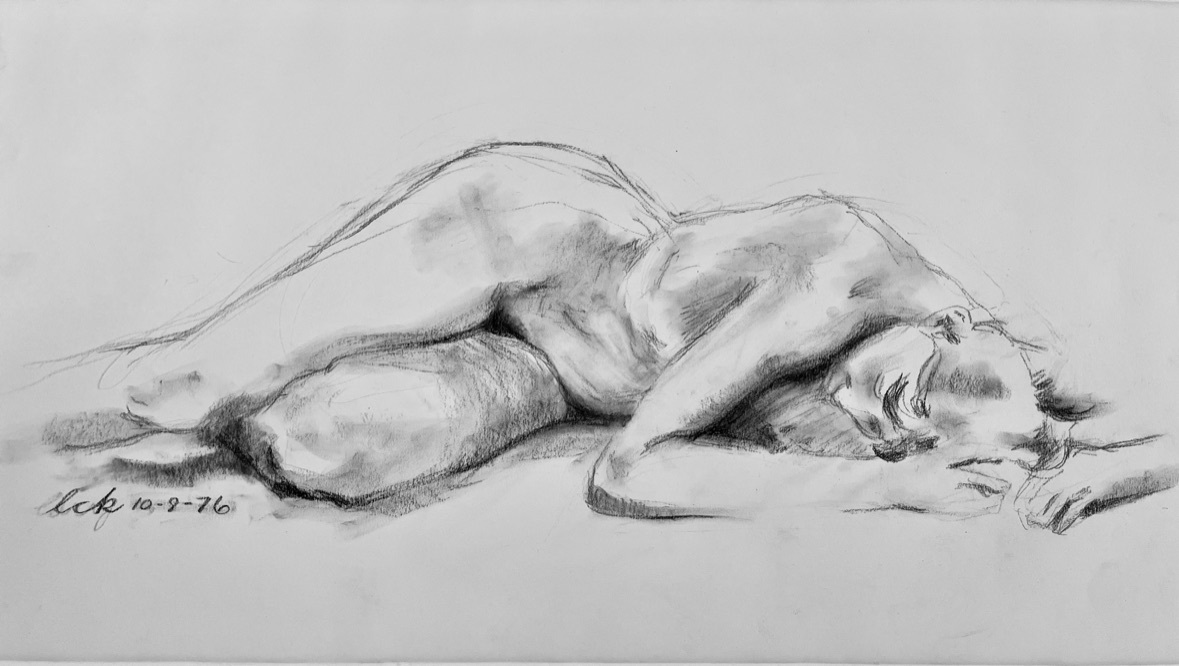

The figure drawing above was drawn by the author as a first-year medical student attending an elective live model art class. We might call this work, “The Side Sleeper”. The human form appears as a disheveled heap in slumber. The three-quarter prone rotation of the upper body twists down to the lateral decubitus position at the hips. The head turns back to a lateral decubitus axis while being flexed and tucked under the right shoulder. While the left leg is flexed along the same sagittal axis, the right leg assumes slight internal rotation as the right knee falls past the left shin. We intuitively recognize this complex posture as a familiar pattern of side sleeping, and the drawing creates a pleasant state of restfulness. The soft, hazy style of the charcoal medium adds to the overall dreamy aura of sleep.

In deconstructing the anatomic axes and posturing of the model in this artwork, we get an inkling of how figure drawing might meld with improving a physician’s grasp of anatomy and kinesiology. This article will explore the developmental stages of figure drawing from childhood, moving to the development of adult artistic rendering of the human figure, and the potential impact of art education within medical education.

The normal progressive milestones of figure drawing in childhood are well established.1–3 Functional creativity is thought to begin at 3 years old; the child begins to reproduce their vision of the world in a drawing. A 2-year-old may be able to draw circles and lines, called the SCRIBBLING stage, but at 3, an attempt will be made to put 2 circles as eyes inside a circle of a head, the PRE-SCHEMATIC stage. Physically, a 2-year-old will grasp a crayon with a full hand grip (point sticking out the ulnar side of a full flexed grip around the utensil), while a 3-year-old will start gaining the ability to use the digital pronator grip of adulthood.

At 4 years old, the “tadpole” figure – 2 lines extending from the bottom of a circle – changes into the more recognizable stick figures. A 5- or 6-year-old will begin the SCHEMATIC stage, and add more complex attributes: fingers, torso, some semblance of clothing and facial details. Although children tend to diverge in abilities thereafter, 8- to 11-year-olds enter the PRE-REALISM stage, showing facial expression, frown or smile or angry eyes, and showing the body in various postures – crude figures running or lying down or holding family hands.

The PSEUDO-NATURALISTIC stage, at ages 11-14, can be a frustrating phase where adolescents try to add shading and perspective, but they can be disappointed when their drawings do not live up to their visual experience. Here is an age where mentorship can build a love of artistic creation rather than abandonment.

If the young adult embraces their artistic skills, they will enter the DECISION-MAKING stage, age 15-18, and evolve their own styles and preferences in drawing and media. This is the dawning of the future adult artist.

As an artist learns to master the human figure, there are three conceptual domains that must ultimately synergize to achieve ideal rendering of the human form.4 First, there is the anatomic, the understanding of the anatomic underpinnings of the body. Second, there is the geometric, where the body is simplified into a collection of interconnected geometric shapes, bowing cylinders for limbs/small and large circles for joints, triangle and circle for skull, and the like. The third domain is the reverse of the former pair, the unseeing of the conceptual, and the embracing of what the eye is truly receiving in vision. This may confound the shapes and structures of the first two domains that the brain is trying to overlay upon the actual visual landscape. For example, the anatomist may want to see upper and lower eyelids in a symmetric almond pattern, but what the eye actually sees may be no lower eyelid at all, lost in shadow and lost in a preconscious attention to pupil size and the blossom of color that is the iris, thus tuning out the features of the lower lid completely. Having mastered all three domains, the artist is ready to unleash their creative renderings with heightened expressiveness.

Finally entering their early 20’s, medical students take notes from sage anatomy professors and encountering the formaldehyde fumes hovering around their lab cadaver. Here, among the budding healers of the corpus, an artist identity can resurface. Does it help a medical provider’s skills to draw the human figure or is it simply an act of personal amusement and escape, turning anatomical study into anatomic art?

In the three domains of figure drawing, there is clear benefit to the student in mastering the anatomy of the body and utilizing drawing to reinforce the three-dimensional placement of those structures. Incorporating the geometric domain of drawing, the medical student achieves a sense of proportion to the anatomic structures. Perhaps most important, using the anatomy and proportionality of the body, the medical student can add the third domain, the culmination of advanced observational skills so crucial to maturing into a gifted diagnostician, the ability to acknowledge what the clinician is actually seeing in front of them, and identifying the positive and negative findings compared to the normative state. This advanced observational stratum, described as Visual Literacy, is the ability to reason physiology and pathophysiology from visual clues.5 It need not just be restricted to the vision, and once arising, the physician should be able to translate the same approach to palpation and auscultation of the patient as well.

What do we see in actual medical education? Medical humanities courses exist in most medical schools. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has recommended integrating medically relevant arts and humanities curricula into medical student education in order to promote physician skills development.6 Art in Medicine courses are a subset within these humanities programs. Art and Anatomy courses are yet an additional small section within these programs. “The most common way in which schools reported doing so was through integration of visual arts-based methods into foundational courses or rotations and through community-building activities such as during orientation week. Such activities remain largely elective, with less than a quarter of schools reporting consistent use of visual arts-based pedagogies in the core required classes or rotations that all students take”.6 University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center has a partnership with the Dallas Museum of Art that teaches medical students to analyze artworks to improve their observation and diagnostic skills. Dell Medical School, at which the author is an affiliate professor, has a Empathy Through Art activity where students create art with cancer patients, caregivers, and staff to develop empathy and therapeutic arts skills.7

Research evaluating these programs is often qualitative, demonstrating positive impact on wellness, creativity, and professional interaction.5 However, there is ample research documenting the improvement in observational skills,5,8 perhaps one of the most important steps in the evolution from fledging student towards a true physician identity. It may be difficult to sort out whether the time spent on anatomic art will advance medical skill acquisition equal to the benefits of other time efforts of medical skill improvement. And yet, studies show clearly that retention and applicable learning are poor with didactic lectures.8 Active learning, which would include figure drawing, is defined as a teaching strategy where students are engaged in the learning process through activities and discussions, rather than passively receiving information (Ref. 9). “Drawing significantly improves memory, retention and recall, outperforming traditional study strategies such as note-taking, listening to lectures, or viewing pre-existing images. Notably, the benefits of drawing persist regardless of artistic ability, making it an accessible and effective learning strategy for all students”.8

It is likely that it will just depend on individual student learning styles and individual student specialty goals. While the author was honing his anatomic skills illustrating for the student note service, his compatriot classmate in art drawing went on to be a plastic surgeon. What patient would not want their plastic surgeon to have a bit of an artist’s eye?

Art and Anatomy courses are offered as electives in many medical schools. Students usually self-select this realm of study in their medical training. The first year of medical school has students hungering to initiate acquisition of the skills of the future clinician. It would not hurt to coax students to include figure drawing as an integral part of their first-year anatomy class studies.